Introduction to Hostile Architecture

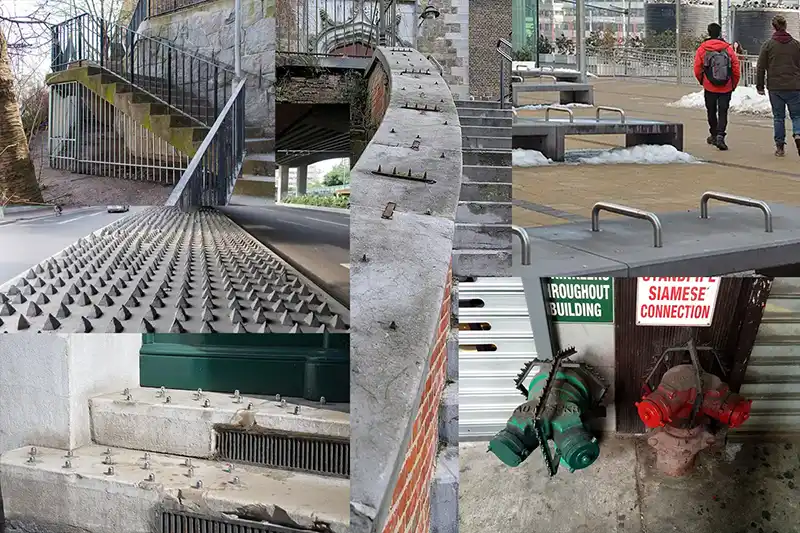

Hostile architecture, or defensive urban design, integrates elements into the urban environment intended to guide or restrict behavior, specifically aiming at preventing actions deemed undesirable by property owners or city planners. This form of architecture has an underlying strategy of remaining inconspicuous to the majority, only impacting targeted behaviors or groups, such as the homeless or skateboarders, by implementing features like anti-homeless spikes or unusually positioned bike racks (UrbanistHQ).

Examples of Hostile Architecture

Detailed Exploration of Hostile Architecture

Types of Hostile Architecture

Hostile architecture manifests in multiple forms, each designed to deter specific behaviors in urban environments:

- Anti-Homeless Spikes: Metal or stone spikes installed in areas where homeless individuals might sleep or sit. These are among the most overt forms of hostile architecture, sending a clear message of exclusion (UrbanistHQ).

- Bench Designs: Benches with armrests in the middle, sloped surfaces, or divided seating are designed to prevent lying down, targeting the homeless population primarily but also affecting the broader public by restricting the use of space (UrbanistHQ).

- Sprinkler Systems: Used as a less permanent solution compared to spikes, sprinkler systems deter people from staying in a place by spraying water at timed intervals. This method has been criticized for its inhumane approach to managing public spaces (Wikipedia).

- Skatestopper Devices: Metal brackets or bumps installed on surfaces to prevent skateboarders from grinding on edges. These devices aim to protect property but also limit the freedom of urban sports enthusiasts (Wikipedia).

- Boulders and Landscaping: Some cities have resorted to placing large rocks or creating uneven landscapes to discourage camping or gathering, subtly altering the environment to influence behavior without direct confrontation (UrbanistHQ).

Logic and Psychology Behind Hostile Architecture

The design and implementation of hostile architecture are grounded in the desire to control public spaces and direct human behavior. The logic stems from a combination of safety concerns, property protection, and aesthetic preferences. This form of urban design leverages psychological deterrents by making environments physically uncomfortable or less accessible for unwanted activities, effectively discouraging specific groups without the need for legal enforcement (UrbanistHQ) (Wikipedia).

Psychologically, hostile architecture can instill a sense of alienation and exclusion among those it targets, particularly the homeless and youth. By prioritizing the comfort and needs of certain groups over others, these designs subtly communicate who is welcome in public spaces and who is not, reinforcing social divides and perceptions of public space ownership (UrbanistHQ) (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

Detailed Alternatives to Hostile Architecture

In response to the ethical concerns raised by hostile architecture, urban planners and social advocates propose several inclusive design strategies that foster engagement and accessibility while still addressing safety and security concerns:

- Inclusive Seating: Design benches and public seating that accommodate various needs, including those of the homeless, without compromising comfort for all users. Seats can be designed to be comfortable for resting without enabling lying down, using gentle slopes or wide armrests (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

- Public Amenities: Incorporating amenities such as public restrooms, drinking fountains, and shelters can make urban environments more accommodating and humane for everyone, including the homeless population, thereby reducing the need for exclusionary designs (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

- Community-Centered Design: Engaging local communities in the design and planning of public spaces ensures that urban environments reflect the needs and values of all users. This approach can lead to innovative solutions that balance security concerns with inclusivity (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

- Environmental Design for Safety: Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) principles can be applied to create spaces that are naturally safe and welcoming without resorting to hostile elements. Strategies include improved lighting, visibility, and natural surveillance, promoting a sense of community ownership and care (UrbanistHQ).

- Flexible Urban Furniture: Incorporating modular and adaptable urban furniture that can serve multiple purposes and accommodate a variety of activities and user groups. This includes moveable seating, adaptable shelters, and multifunctional structures that encourage positive use of public spaces (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

Public Perception and Controversy

Hostile architecture often sparks public debate, with critics arguing it makes public spaces unwelcoming to everyone, particularly targeting vulnerable populations. Meanwhile, proponents believe it helps maintain order and safety by clearly delineating spaces and their intended uses. Artistic and social responses have emerged, such as public awareness campaigns identifying hostile design elements (Wikipedia).

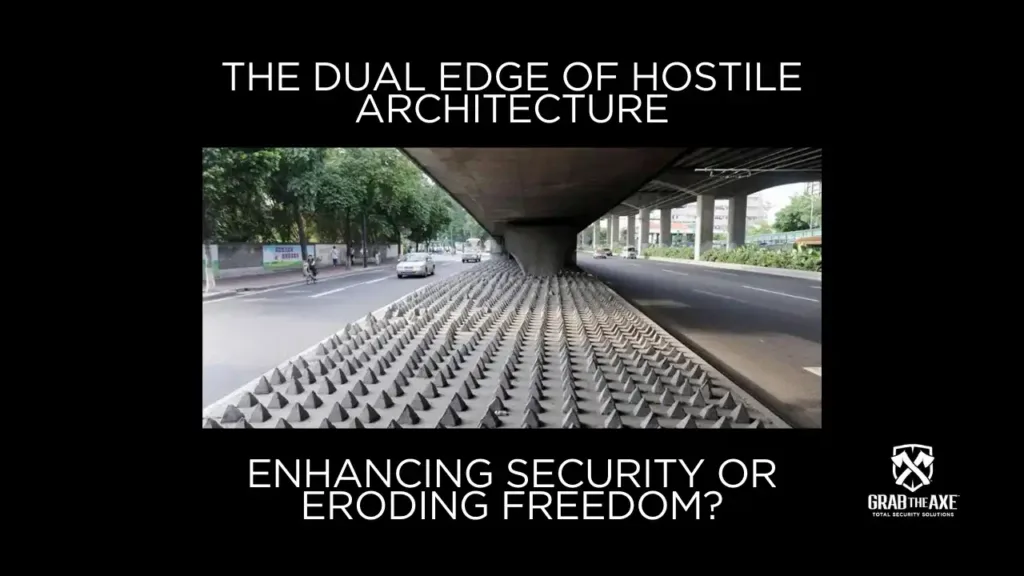

The Role of Hostile Architecture in Security

While aimed at enhancing security by deterring undesired behaviors, hostile architecture raises ethical concerns. It addresses symptoms rather than root causes, such as homelessness, by merely shifting the visibility of these issues rather than offering solutions. It signifies a significant financial investment in controlling public space use that might be better directed towards addressing the underlying social issues (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

Critiques and Alternatives

Critics argue that hostile architecture represents a superficial approach to dealing with complex social issues like homelessness, often resulting in an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality that does not solve the underlying problem. Alternatives suggest a shift towards more inclusive urban design practices that foster community engagement and address social issues directly, rather than excluding certain groups from public spaces (Viterbi Conversations in Ethics).

Hostile architecture reflects a critical intersection between urban design and societal values, revealing much about how communities prioritize space, security, and inclusivity. For organizations like Grab The Axe, understanding these dynamics is crucial in advocating for designs that balance security needs with ethical considerations and societal well-being. The challenge lies in reimagining urban spaces that are secure yet inclusive, underscoring the importance of addressing root causes of social issues rather than their manifestations in public spaces.

References:

Rosenberger, R. (n.d.). Urbanism 101: Hostile Architecture. The Urbanist. Retrieved from https://www.theurbanist.org

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, March 29). Hostile architecture. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hostile_architecture

Nussbaum, Z. (n.d.). Hostile Architecture: The Ethical Problem of Design as a Means of Exclusion. Viterbi Conversations in Ethics. Retrieved from https://vce.usc.edu/hostile-architecture-the-ethical-problem-of-design-as-a-means-of-exclusion/

To Learn More:

Perimeter Security for Your Business: Top 5 Essential Solutions

Essential Guide to Physical Security Assessment for Businesses: Top 10 FAQs Answered

Business Security Services Phoenix AZ: A Strategic Approach to Safeguarding Your Enterprise

This Post Has One Comment

Pingback: Business Consulting for Small Businesses: Top 10 Key Benefits

Comments are closed.